Marie Lourdes Charles, EdD, RN-BC, FNYAM1* Marjory David, MSN, FNP-BC, RN2, Marlene St. Juste, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC, GC-C3, Judy Michel, MSN, ANP-BC, SANE4

1Associate Professor Lienhard School of Nursing College of Health Professions Pace University 163 William Street Room 515 New York, NY 10038.

2Adjunct Clinical Instructor Pace University College of Health Professions Lienhard School of Nursing 163 William Street Room 515 New York, NY10038.

3Lecturer Yale School of Nursing Orange, CT.

4Nurse Practitioner Harmony Healthcare Long Island, Hempstead, NY 1155.

*Corresponding author: Marie Lourdes Charles. Associate Professor Lienhard School of Nursing College of Health Professions Pace University 163 William Street Room 515 New York, NY 10038.

Received: December 06,2023

Accepted: December 12, 2023

Published: December 18, 2023

Citation: Charles, ML; David, M; St. Juste, M., Michel, J. (2023) “Perceptions and experiences of Registered Nurses caring for human trafficking victims in acute care settings: An integrative review.”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 3(2). DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR/053.

Copyright: © 2023 Marie Lourdes Charles. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Purpose:

Human trafficking is a crime that may involve force, fraud, or coercion to compel a person into commercial sex acts or labor or services against their will. The purpose of this integrative review was to synthesize the literature on the perceptions and experiences of Registered Nurses (RNs) caring for victims of human trafficking in an acute care setting.

Design:

This integrative review utilized the Whitmore and Knalf model.

Method:

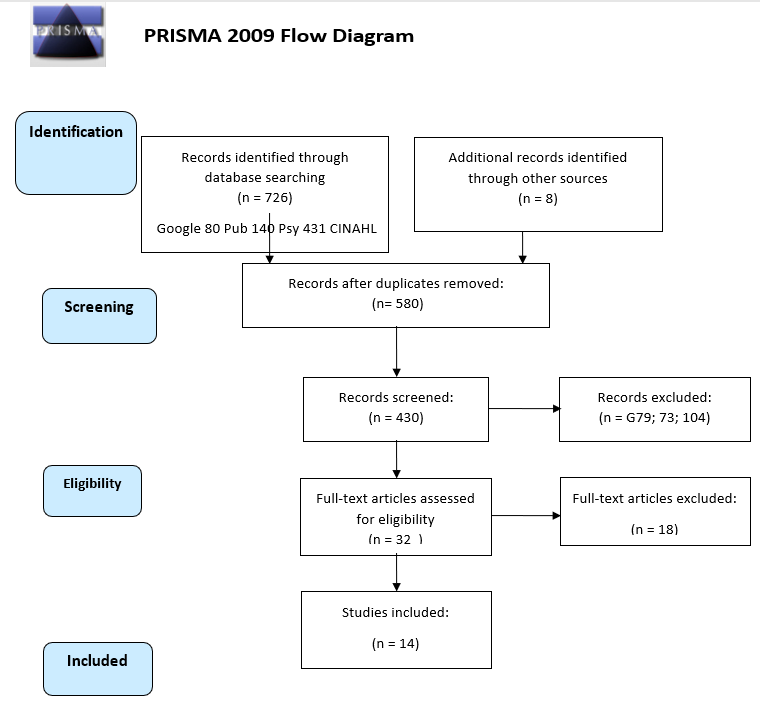

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was used as a guide for conducting the literature search. The initial search resulted in 726 studies related to human trafficking; 14 publications met the inclusion criteria. The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) and the Joanna Briggs Institute Tool were utilized to appraise the articles which consisted of quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods studies, and a scoping review.

Results:

Most of the literature did not include RNs experiences caring for this population in acute care settings. Identification of victims was the main challenge due to attitudes and lack of skills/ knowledge. Seven themes emerged: identifying red flags, approaching potential victims, using standardized screening tools, recognizing common chief complaints on specific health issues, documenting the encounter in the electronic medical record, health care providers' negative attitudes, and referring victims to available resources.

Conclusion and Implication:

Addressing healthcare, social, and mental health factors required a multidisciplinary approach because victimization creates all types of trauma. Educational programs could improve knowledge resulting in increased self-efficacy. Access to education could increase clinical competence, improve patient care, and advocacy for this population, which could lead to policy development.

What this article adds to the literature:

Introduction:

Human trafficking (HT) refers to a crime where perpetrators exploit adults or children by forcing them to perform labor or engage in commercial sex (United States Department of State, 2023). Sex and labor trafficking differ due to the diversity of clients, victims, and consequences (Costa et al., 2019). The number of human trafficking victims is not determinable because it is a clandestine crime (Lamb-Susca & Clements, 2018). Victims of trafficking are transported nationally and internationally to be exploited through forced sex work, domestic servitude, or for labor in agriculture, car washing, construction, and factory work (Ross et al., 2015). In the United States, during 2021 to 2022, a total of 2,198 incidents of human trafficking were reported to United States Attorneys (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2022). Lack of training, lack of investigations, and ineffective laws contribute to the low detection of human trafficking (Leslie, 2018). Fear and shame may cause individuals not to readily identify themselves. Victims might assume that providers would be judgmental, indifferent, or insensitive, making treatment and rescue more complex (Baldwin et al., 2011). Therefore, healthcare professionals may not be aware that these patients are victims and may miss relevant clinical cues. While being trafficked, victims encounter the healthcare system with the emergency department being the most visited setting for medical treatment. Emergency department clinicians are in a unique position to identify victims due to their intersection with violence and abuse.

Background:

According to McAmis et al. (2022), approximately 88% of trafficked victims receive healthcare services during their captivity. Lamb-Susca and Clements (2018) reported that these victims frequent or utilize hospitals, clinics, dental offices, obstetrics and gynecology clinics, primary care physicians, Planned Parenthood, mental health clinics, substance abuse centers, and suicide prevention hotlines. However, emergency department nurses might be the providers with whom they spend the most time, which may facilitate better assessment. These victims may be reticent because of the shame associated with having been involved in sex work, post-traumatic stress disorder, and connections to the traffickers. Nevertheless, most people consider nurses trustworthy. Nurses may be in a better position to question and discuss difficult issues with patients. Lamb-Susca and Clements (2018) also highlighted the importance of nurses having the right attitudes as this could be beneficial in gaining victims’ trust leading to victim identification.

A lack of identification is a major barrier to rescue. Although healthcare providers (HCPs) are key to identifying victims, there is limited research on how HCPs interface with human trafficking (Hainaut et al., 2022). Additionally, many of these studies were conducted in the community. The majority of the studies included in this integrative review consisted of self-reported questionnaires or surveys and screening tools. Self-reported surveys have the potential to be skewed as participants’ responses may reflect what they believe researchers expect as answers (Rosenman, Tennekoon, & Hill, 2011). The purpose of this integrative review was to synthesize the literature on the perceptions and experiences of Registered Nurses (RNs) caring for human trafficking victims.

Problem Statement:

Human trafficking is a national and international issue. Victims of trafficking require specialized acute, psychosocial, and legal care, which facilitate rescue and recovery (Wolf, Perhats, & Delao, 2022). Nurses lack education and training to identify and care for these victims. The research question is:

ow does the perception of human trafficking impact nurses’ ability to identify and care for victims?

Method:

The Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) method was utilized to guide the analysis, synthesis, and conclusion of this integrative review. This method facilitates incorporating quantitative, qualitative, and theoretical research, including empirical and non-empirical articles. It consists of problem identification, a literature search, quality appraisal, data analysis, and result presentation. A preliminary literature search led to identifying human trafficking as a global health issue necessitating further inquiry. Gaps in the literature related to nurses’ understanding of human trafficking were evident. Therefore, an integrative review was selected to synthesize the available information (Whittemore & Knalf 2005). To improve the rigor of this review and make it applicable to practice, education and research, the authors focused on RNs encountering victims in healthcare settings. As the largest number of healthcare professionals, RNs can impact the health outcomes for HT victims.

Search:

Electronic searches of CINAHL, PubMed, Psych Info, and Google Scholar resulted in 726 studies using the following key words: human trafficking, sex trafficking, labor trafficking, and nurses. Authors utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to conduct the literature search. Duplicates were removed, title and abstract screening led to 694 articles excluded. Hand searches led to eight articles, resulting in a total of 32 full-text articles being assessed for eligibility. Inclusion criteria: (1) Participants were RNs working in inpatient settings including emergency departments (EDs); (2) If other healthcare practitioners were included in the research, information regarding RNs was reported separately; (3) Nonexperimental and experimental research articles published between 2000 and 2023; and (4) peer reviewed. Studies were excluded if they were designed for continuing education credits. Fourteen publications met the inclusion criteria.

Quality Appraisal:

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was utilized to appraise most of the articles and the Joanna Briggs Institute Tool was used for the scoping review. This approach was in accord with Whittemore and Knalf’s (2005) recommendations to utilize a tool appropriate for appraising multiple methods and individual tools for outliers. Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods studies, and a scoping review were included in this integrative review. Therefore, the MMAT was relevant; it consists of five questions each for assessing qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled trials, quantitative non-randomized, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods study designs. The quality of the studies was moderate to good.

Literature Review:

Most of the studies consisted of self-reported surveys and utilized convenience sampling. For example, a cross-sectional survey was conducted in England (Ross et al., 2015). Participants included 782 National Health Service healthcare professionals of which 36.4% were nurses. The survey used a questionnaire that asked about prior training and contact with potential victims of trafficking, perceived and actual knowledge, confidence about responding to HT, and interest in future training. Most respondents reported they lacked the knowledge necessary to identify or assist potential victims. Additionally, many reported they lacked confidence in making appropriate referrals. Thirteen percent of participants reported prior contact with HT victims. Those who were most likely to identify victims had prior training. More than 70% of the participants expressed an interest in training. Similarly, Coppola et al. (2019) conducted a study in New Jersey using a cross-sectional design. The sample consisted of 734 RNs, representing a very low response rate of 0.6%, since the online survey was sent to about 120,000 RNs. Like the findings of other studies, several nurses reported a lack of training and desired additional education. Results also revealed that training was not consistent across the state. Although New Jersey mandates online training for healthcare providers, there is no education specifically for RNs. Coppola et al. (2019) highlighted that RNs have specialized patient assessment skills not addressed in the statewide online training.

Another study utilizing self-reported surveys examined the knowledge of HCPs on HT in the healthcare setting. McAmis et al. (2022) evaluated prior training and knowledge as well as the need for future training, with 6,603 participants responding, of which, 9.8% (N=650) were nurses and 4.3% (N=281) were nurse practitioners. The findings of this study were in alignment with Ross et al. (2015) where participants reported lacking education and training. Although the majority believed they would have benefitted from training, less than half of the respondents had received training. Comparable to the study conducted by McAmis et al. (2022), Leslie (2018) found that training was not mandated consistently across the United States nor was training to identify victims standardized. Of note, some states like Michigan, Florida, and Texas mandate HT education to maintain licensure for nurses, nurse practitioners, and social workers. Additionally, Wolf et al. (2022) reported that only six states require education on caring for patients who encounter violence or abuse for licensure.

Several other studies in this integrative review reported that nurses lacked education or training (Long & Dowdell, 2018; Ramnauth et al., 2018; Sangha & Birkholz, 2023; and Wolf et al., 2022). The lack of education about HT was evident in Long and Dowdell’s study. All the nurses reported they had never “screened, identified, or knowingly treated a victim of human trafficking” (Long & Dowdell, 2018, p. 378). Additionally, all the nurses interviewed believed that most victims of HT were young women and foreign born. These misconceptions of victims impede the identification and treatment of this group. The nurses also reported not having received any education at the undergraduate level or during practice.

Ramnauth et al. (2018) conducted a quantitative cross-sectional study, utilizing a self-reported survey, which was distributed to nurses actively working. Only nurses were recruited, 164 RNs responded. Ramnauth et al. (2018) found knowledge gaps regarding HT and overall, nurses lacked awareness and guidelines to provide appropriate care. Nevertheless, results indicated that education and training increased nurses’ confidence in caring for this population.

Researchers utilizing different methods found similar results regarding factors inhibiting identification. Recknor, Gemeinhardt & Selwyn (2018) conducted a qualitative study with 44 HCPs of which 12 were nurses. A semi-structured interview format was utilized. Recknor et al. (2018) indicated that most of the qualitative studies investigated sex trafficking of children and adults, omitting labor trafficking. Moreover, the studies did not focus specifically on healthcare professionals. The following themes emerged: Prevalence of victims identified in health care; Human-trafficking awareness and knowledge; Labor-trafficking awareness; Stereotypes, stigma, and shame; and Lack of adequate community resources and health setting protocols.

In keeping with the literature in this integrative review, Recknor et al. (2018) found that healthcare professionals reported low numbers of HT victims for their sites. However, this was a significant finding for this study as Houston has very high rates of this crime. Recknor et al. (2018) examined the dilemma of what to do with victims once they were identified. For example, the lack of community resources for HT victims, a barrier not emphasized in the general literature, is two-fold. From the victims’ perspective, there is a sense of hopelessness, in that they believe there may not be any help or a safe place to go; so, they do not disclose. On the other hand, healthcare professionals may perceive the lack of resources and hesitate to screen or identify victims.

Another qualitative study conducted by Ruiz-Gonzalez et al. (2022) investigated experiences of 14 midwives utilizing semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus groups. Sex trafficking was selected as the subject matter for the inquiry since it is the most encountered form of HT. This study differed from others included in this review because all participants were required to have cared for sex trafficking victims, which gave them a unique perspective. Two themes emerged from the data: Sex trafficking: A camouflaged reality on the invisible spectrum and A thirst for attention in the aftermath of violence. These participants reported similar challenges identifying victims. Ruiz-Gonzalez et al. (2022) discussed that possible red flags could be the patient’s oral report, body language, and physical examination do not correlate. Furthermore, psychological trauma might cause victims to have warped views and remain with traffickers. Several midwives requested practical education such as role play, simulation, and training from experts. Some of the participants recommended the use of clinical practice guidelines and information on community resources.

Studies regarding sex trafficking were predominant in the literature. Pederson and Gerassi (2021) conducted a qualitative study with 23 HCPs of which seven were nurse practitioners to examine the relevance and utility of indicators or red flags. They found that many indicators were not viewed as relevant or were disregarded by HCPs. For example, HCPs did not always consider repeated sexually transmitted infections, bruises, tattoos as red flags. Another indicator often overlooked was an older adult female accompanying several younger women seeking care. Consistently assessing these signs is important, especially in complex situations.

Technological advances have led to the discovery of new approaches for identifying HT victims. A mixed method study discussed using precision medicine and biometrics (palm readers; fingerprinting; iris scans; and genetic data) for identification, data sharing across medical centers, and continuity of care (Katsanis et al., 2019). Biometrics offers HCPs the capacity to identify patients who have made multiple visits to healthcare centers, which can provide more reliable medical histories. Risks of using biometric data include breach of privacy, access to data by law enforcement, and less trust in healthcare professionals and institutions. Components of the study were an electronic health record (EHR) search, semi-structured interviews, and physician and nurse surveys. The EHR search was conducted to identify markers in the medical records indicating patients who met the following criteria: “(a) identity unknown at admission to emergency room, (b) fake identification used, or (c) adult individuals who appear with a controlling companion” (Katsanis et al., 2019, p.5). However, these markers or codes were not evident in the EHRs. Findings that emerged from the interviews were: (a) the term “human trafficking” incorporated many categories of clients; (b) providers were unaware of institutional resources or policies; (c) there were limited medical record tools and codes to use for documenting HT; and (d) many interviewees believed biometrics to be overly invasive and not appropriate for these victims. The physician nurse survey results were similar to the findings of other studies in this review. Providers reported not feeling confident to care for HT victims. Moreover, most respondents expressed that continuity of care was a major issue for this population and biometrics might be beneficial in these cases.

Several studies focused on education to resolve issues identifying HT victims. Many of the educational interventions provided nurses with a better comprehension of HT, differences between labor trafficking and sex trafficking, and of who is at risk of becoming a victim. Some interventions provided information on state and federal laws, as well as community resources available to HT victims (Berishaj, Buch, & Glembocki, 2019). A pilot study was conducted using a 4-hour conference format. A multidisciplinary approach was utilized to present the conference to nurses. Professionals from diverse backgrounds presented, including nurses, an attorney, and a Homeland Security police officer (Berishaj et al., 2019). Results were in alignment with other studies reviewed, post conference, nurses reported increased confidence identifying and caring for trafficking victims.

Sangha and Birkholz (2023) found that human trafficking educational programs could improve nurses’ knowledge and self-efficacy. Seventy-two nurses participated in the study. The intervention was a 1-hour slide presentation. Findings indicated nurses believed their assessment skills and confidence to treat this population increased after the intervention. This study was significant because afterwards the healthcare facility reported receiving identification of more potential and actual HT victims and referrals to the forensic department. Other modalities were found to be as effective in increasing nurses’ knowledge and confidence. Murphy (2022) implemented an educational intervention, correlating to Sangha and Birkholz’s (2023), aimed at improving knowledge and self-efficacy. Twenty-two emergency department nurses participated. However, Murphy’s (2022) educational intervention was a hybrid format. The online training took about 20 minutes to complete, followed by bi-monthly in-person group presentations. Murphy’s (2022) study included providing education on utilizing a more structured patient safety screening tool, consisting of five assessment questions about HT. This tool facilitated all emergency department patients to be screened. Overall, nurses reported an increase in self-efficacy. Although information about the validity of the screening tool was not detailed, Murphy (2022) supported the use of screening tools as a successful means in the identification of potential victims.

Currently, there are different protocols or tools used for identifying victims, and many have not been validated (Hainaut et al., 2022; Leslie, 2018). Some healthcare institutions have developed their own guidelines and tools. Leslie (2018) argued having many different protocols makes establishing a national standard for identification and treatment challenging. A scoping review by Hainaut et al. (2022) concluded there was a need for standardizing screening tools. Hainaut et al. (2022) indicated that many identification documents and strategies were not validated, nor did the authors of the studies reviewed focus on the healthcare setting. Of the screening tools included in their study only six had been validated in peer-reviewed literature for all forms of trafficking, including labor and sex trafficking in all populations. The tools were not general enough to be applicable to different types of trafficking or populations.

Some researchers recommended specialized education. Wolf et al. (2022) conducted a quantitative exploratory, descriptive study with 1,824 emergency department nurses. The majority of the nurses (96,9%) reported that the lack of training resulted in missed opportunities to collect and preserve evidence. Over 68 percent of the nurses believed that training on the management and care of HT victims was necessary. Wolf et al. (2022) supported the need for forensic education and clinical skills for providing care to patients who present with trauma from violence. Forensic education could help nurses who are uncomfortable or lack confidence in providing trauma-informed care. Furthermore, Wolf et al. suggested education should include strategies to address stigma and nurse bias.

Results:

Seven themes emerged from the synthesis: 1) identifying red flags, 2) approaching potential victims, 3) using standardized screening tools, 4) recognizing common chief complaints or specific health issues, 5) documenting the encounter in the electronic medical record, 6) healthcare providers’ negative attitudes, and 7) referring victims to available resources.

Identifying red flags:

The literature converged on identification as the major issue hindering providing care to HT victims, especially in the healthcare setting (Hainaut et al., 2022). Assumptions that victims were predominantly foreign born, female, and young led to low rates of identification. Few nurses believed victims could be male (Long & Dowdell, 2018; Ramnauth et al. 2018). Red flags included, multiple sexually transmitted infections, pregnancies, abortions, or sexual partners, signs of torture, tattoos indicating ownership, and the person accompanying the patient refusing to leave them alone for physical examinations (Pederson & Gerassi, 2021; Ramnauth et al., 2018). Red flags should be indicators for healthcare providers to do more thorough assessments. Studies which included educational programs found nurses’ knowledge, confidence, and self-efficacy in identifying HT victims increased post interventions (McAmis et al., 2022; Wolf et al., 2022)

Approaching potential victims:

Nurses reported being hesitant to have difficult conversations with actual or potential victims. Many nurses expressed a lack of knowledge or skill on how to ask victims about their experiences (Ross et al., 2015; Ruiz-Gonzalez et al., 2022). Difficulty on what questions to ask or framing questions were some of the barriers to identifying victims. Despite having suspicions, nurses did not feel comfortable asking probing questions or persisting once the patient responded no. Additionally, victims’ confidentiality and not utilizing interpreters when victims have limited English proficiency complicated approaching patients with questions regarding forced sex or labor work (McAmis et al., 2022; Ruiz-Gonzalez et al., 2022).

Using standardized screening tools:

The need for screening tools was evident throughout this inquiry. Many studies discussed utilizing assessment guides or protocols, embedded in the electronic medical record, to help screen all patients who present to emergency departments (Murphy, 2022). This would increase identifying and treating victims (Murphy, 2022). Some healthcare institutions developed their own clinical guidelines or logarithms (Coppola et al., 2019). The consensus was that protocols lacked validation or standardization. Most researchers recommended establishing a national screening tool to be used in assessing identified or potential victims.

Recognizing common chief complaints or specific health issues:

Specific problems with assessing victims were recognizing common chief complaints or health issues, such as physical injuries, dental disease, malnutrition, psychological distress, sexually transmitted infections, or substance use disorders (Long & Dowdell, 2018; McAmis et al., 2022; Sangha & Birkholz, 2023). Almost every body system may be affected from being a victim of HT. Additionally, inappropriate assessments or being unaware of potential triggers may increase patients’ emotional and psychological trauma.

Documenting the encounter in the electronic medical record:

Nurses reported a lack of guidance on documentation or institutional policies about HT. Several studies discussed that nurses requested training on documenting chief complaints and red flags (McAmis et al., 2022). HT is crime and proper documentation could lead to the prosecution of perpetrators, making recording assessments even more crucial. Murphy (2022) highlighted that documenting patient assessments was particularly challenging for nurses. Limited English proficiency was also a hinderance to proper documentation of encounters with trafficking victims (Recknor et al. 2018).

Healthcare providers’ negative attitudes:

Negative healthcare professionals’ attitudes and perceptions about victims hampered identification and treatment. Nurses’ personal biases were mentioned in several of the studies (Wolf et al., 2022; Recknor et al., 2018; Sangha & Birkholz, 2023). At times, misconceptions that individuals who engaged in prostitution were hard and tough prevented nurses from noting warning signs and cues. Some healthcare professionals sometimes did not believe that patients were victims of HT (McAmis et al., 2022). Several of the studies reported that nurses assumed traffickers accompanying victims would be older males, aggressive, or overbearing. Meanwhile, this was not the typical presentation.

Referring victims to available resources:

Patients’ clinical issues were compounded by financial, mental health, legal, and social factors. Perceived inadequate community resources led providers not to screen victims because they did not know what to do with the information or the person afterwards (Recknor et al 2018; Ruiz-Gonzalez et al., 2022). Nurses reported needing training on how and when to contact law enforcement agencies. At times, providers did not identify victims because of obligations to notify authorities. Patients in turn did not disclose because victims of sexual trafficking feared being arrested for prostitution, or other HT victims feared being judged. Furthermore, they believed referrals and resources to help them were unavailable. Nurses expressed that counseling resources for victims were absent (Ramnauth et al., 2018). Providers also experienced burn out and stress disorders from trying to help human trafficking victims because of the lack of resources for follow-up (Ruiz-Gonzalez, 2022).

Discussion:

Failure to identify victims may result in missing opportunities to counsel and assist the victim in leaving the situation (Recknor et al., 2018). At times, victims may not be able to adhere to treatment plan and follow-up; therefore, it is important that providers complete as much as possible in one visit (Recknor et al., 2018). Educational programs were found to increase nurses’ knowledge, confidence, and self-efficacy. Education improved nurses’ abilities to perform patient interviews and ask questions confidentially, non-judgmentally, and in more sensitive ways. Documentation is crucial in these cases because they could facilitate criminal proceedings and bring perpetrators to justice.

Human trafficking victims have many needs which must be prioritized to provide comprehensive care, such as medical, psychological, and physical safety issues. Once victims are identified and assisted out of the slavery cycle, HCPs must consider that patients’ priorities and their own may not intersect. HCPs are focusing on medical care while patients may be focusing on safety issues for themselves and their families. Victims are often ashamed of their experiences and prefer that their families do not find out. Healthcare professionals can help by maintaining privacy, listening to concerns and feelings victims share. Acting as mentors and affording victims protection encourages receptiveness to treatment plans. This might create a more conducive environment to self-care recommendations.

Effective care of HT victims warrants a multidisciplinary approach. Victimization creates psychological, social, legal, and economic trauma aside from medical injuries. After being enslaved some victims require housing, food, childcare, or legal counsel to reintegrate back to society. Therefore, HT education and training should encompass various disciplines and professions. Community resources are currently ill-equipped to unequivocally address victims’ needs, placing additional stressors on HCPs. Questions remain as to what to do with victims after they have been treated for medical injuries. HT is a major social issue, towards which policy makers and legislators should intervene to bring about change.

Limitations:

Most of the studies selected in this integrative review focused on the emergency department which could have skewed results. Including other subspecialties might have revealed different outcomes or perspectives. Expanding inclusion criteria to other healthcare professionals might have provided insight on approaching human trafficking from a multidisciplinary lens.

Conclusions:

This integrative review examined the experiences and perceptions of registered nurses caring for HT victims. Findings revealed that care of this population required multidisciplinary management to address healthcare, social, and mental health factors. Results indicated identification as the major impediment. The research examined institutional barriers, such as the lack of clinical protocols, and supports initiatives to standardize and implement screening and assessment tools.

Education and training cannot be overemphasized. They have the potential to decrease negative outcomes for victims of HT and to break the cycle of abuse. The first step in rescuing these individuals is identification; recognizing red flags and nuances indicating their enslavement. Stigmas, bias, and negative attitudes have caused nurses to dismiss some relevant HT indicators. Nevertheless, nurses can encourage patients’ trust and create conditions that foster disclosure. Benefits of education extend from the victim to the healthcare professional. Increased knowledge has a direct impact on nurses’ self-efficacy and confidence. Equipping nurses with applicable knowledge and tools decreases burn out and stress for practitioners encountering these patients.

Implications:

Healthcare professionals, educators, and leadership can use the results of this review to develop improved training in HT identification and treatment for nursing and other providers. Access to education could increase clinical competence and patient care for this population, which could lead to policy development.

Contributors MLC and MD conceived the study and conducted the literature search. MS and JM appraised the quality of the selected articles and studies. MLC conducted data analysis. MLC and MD provided overall supervision of the study. MLC, MD, MS, JM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised later drafts and approved the final manuscript. All authors granted approval for the publication of this manuscript.

|

Citation |

Purpose |

Design |

Sample |

Measures |

Findings |

|

Berishaj, K., Buch, C., & Glembocki, M. M. (2019). The impact of an educational intervention on the knowledge and beliefs of registered nurses regarding human trafficking. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 50(6), 269-274. U.S. |

To determine the effect of an educational intervention on nurses’ knowledge and beliefs on HT. |

Quasi experimental |

93 RNs |

Self-report survey 4-hour conference delivered by nursing, law, and criminal justice. |

A comparison between pre and post-tests indicated a significant increase on 17 of 19 items, demonstrating the intervention improved nurses’ knowledge on HT. |

|

Coppola, J. S., Cantwell, E. R., Kushary, D., & Ayres, C. (2019). Human trafficking: Knowledge and awareness in nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Practice Applications & Reviews of Research, 9(1), 40-49. U.S. |

To examine nurses’ familiarity, awareness, and ability to recognize, assess, and refer potential HT victims in their communities. |

Mixed Method |

734 RNs |

0.6% Response rate. Self-reported survey |

Most of the respondents reported being familiar with HT. However, 41.73% reported not knowing whether they had cared for an HT victim. 63.06% reported not having received HT training. 86.42% reported an interest in attending HT education. Healthcare professionals who believe HT is a problem in their communities were more likely to address it in their clinical practice. Education also had a similar impact on respondents addressing HT with patients. |

|

Hainaut, M., Thompson, K. J., Ha, C. J., Herzog, H. L., Roberts, T., & Ades, V. (2022). Are screening tools for identifying human trafficking victims in health care settings validated? A scoping review. Public |

To determine tools which exist to identify HT victims in healthcare settings and whether these |

Scoping Review |

8 studies |

Quantitative and/or qualitative research studies. Included populations of all ages, all genders, and all geographic locations |

The lack of standardized search terminology led to the identification of a limited number of studies. Furthermore, there was an underrepresentation of research on HT in the healthcare setting. Most of the |

|

Health Reports, 137 (1_suppl), 63S-72S. |

tools have been validated. |

|

|

|

research concentrated on identifying sex trafficking victims and omitted labor trafficking. |

|

Katsanis, S. H., Huang, E., Young, A., Grant, V., Warner, E., Larson, S., & Wagner, J. K. (2019). Caring for trafficked and unidentified patients in the EHR shadows: Shining a light by sharing the |

To investigate the use of precision medicine, biometrics, or genetic information to |

Mixed Method |

9 interviews With 3 RNs Survey Respondents 162 MDs 738 RNS |

Three prong study: (1) EHR search for key terms indicating HT conducted November 2016; (2) Semi- |

Response rate was 16.5% for the survey. Of which, 12.2% reported being aware of indicators of HT. 12.8% expressed confidence in their ability to provide trauma informed care. Over |

|

data. PloS one, 14(3), e0213766. U.S. |

identify trafficked persons to facilitate continuity of care. |

|

|

structured interviews with physicians and RNs conducted Summer of 2017; and (3) Self-report survey conducted December 2017. |

85% were unfamiliar with community resources or non-medical assistance. Eight themes emerged from the interviews. Authors concluded there was a lack of knowledge and cohesive approach to providing healthcare to HT victims. |

|

Long, E., & Dowdell, E. B. (2018). Nurses' perceptions of victims of human trafficking in an urban emergency department: a qualitative study. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 44(4), 375-383. U.S. |

To examine the perceptions of emergency nurses about human trafficking, prostitution, and victims of interpersonal violence (IPV) so that they can better identify and screen for these victims. |

Qualitative |

Ten registered nurses |

Semi-structured interviews |

Nurses reported not screening for HT, even though they believed it occurred in the patient population. All the nurses reported that victims come from different countries and are young and female. Nurses were more comfortable identifying and screening victims of IPV versus HT. Most nurses did not consider prostitutes to be victims of HT. Participants reported that prostitutes had chosen their lifestyle. Many used their education on how to identify |

|

|

|

|

|

|

and care for IPV victims and applied it to HT victims. |

|

McAmis, N. E., Mirabella, A. |

To determine the self- reported HT knowledge levels of healthcare providers. |

Mixed |

6,603 |

Self-reported |

Less than half (42%) of the |

|

C., McCarthy, E. M., Cama, |

method |

respondents |

survey. |

respondents reported having |

|

|

C. A., Fogarasi, M. C., Thomas, |

|

including |

Descriptive |

received HT training while |

|

|

L. A., ... & |

|

physicians |

statistics and |

93% reported they would have |

|

|

Rivera-Godreau, I. (2022). |

|

(33.7%), |

content analysis |

benefitted from training. |

|

|

Assessing healthcare provider |

|

medical |

|

Healthcare providers lacked |

|

|

knowledge of human |

|

students |

|

HT knowledge and were |

|

|

trafficking. PLoS one, 17(3), |

|

(13.6%), |

|

unfamiliar with |

|

|

e0264338. U.S. |

|

nurses (9.8%) |

|

traumainformed care. There |

|

|

|

|

N=650. PA |

|

were differences in training by |

|

|

|

|

students |

|

age group with 51-60 year old |

|

|

|

|

(7.0%), |

|

group reporting having |

|

|

|

|

paramedics |

|

received the most training in |

|

|

|

|

(6.1%), social |

|

comparison to younger and |

|

|

|

|

workers |

|

older respondent groups. |

|

|

|

|

(5.7%), |

|

Respondents from the |

|

|

|

|

residents |

|

Midwest also reported higher |

|

|

|

|

(5.5%), |

|

training levels. Of the |

|

|

|

|

physician |

|

respondents, nurse |

|

|

|

|

assistants |

|

practitioners had the highest |

|

|

|

|

(5.1%), EMTs |

|

level of knowledge. |

|

|

|

|

(4.9%), nurse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

practitioners |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(4.3%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

N=281, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

nursing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

students (2.2%), medical assistants (1.3%), and fellows -0.7% |

|

|

|

Murphy, M. C. (2022). |

To determine |

Quality |

22 Registered |

Pre/Post Self- |

Intervention was both |

|

Supporting emergency |

the effect of an |

Improvement |

Nurses |

report Self |

inperson and virtual. Results |

|

department nurse’s selfefficacy |

educational |

Project |

|

Efficacy |

indicated the educational |

|

in victim identification through |

intervention |

|

|

Survey. |

intervention increased self- |

|

human trafficking education: A |

and |

|

|

Bandura’s |

efficacy in victim |

|

quality improvement project. |

implementation |

|

|

Social |

identification and increased |

|

International Emergency |

of HT |

|

|

Cognitive |

comfort utilizing the |

|

Nursing, 65.101228 U.S. |

screening tool |

|

|

Theory |

screening tool. |

|

|

on nurses’ self- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

efficacy in the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

department. |

|

|

|

|

|

Pederson, A. C., & Gerassi, L. |

To explore the |

Qualitative |

23 |

Semi-structured |

Healthcare providers did not |

|

B. (2022). Healthcare |

barriers to |

|

participants. |

interviews. |

always consider indicators |

|

providers’ perspectives on the |

identifying sex |

|

16 medical |

|

such as multiple STIs, sexual |

|

relevance and utility of |

|

|

assistants and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

recommended sex trafficking |

trafficking |

|

nurse practitioners. |

Data collected |

partners, or frequent |

|

indicators: A qualitative study. |

victims, and |

|

between Fall |

abortions as red flags. |

|

|

Journal of Advanced Nursing, |

(2) to examine |

|

2018 to |

They believed these |

|

|

78(2), 458-470. U.S. |

how |

|

Spring 2020 |

indicators to be |

|

|

|

healthcare |

|

|

common in the patient |

|

|

|

providers |

|

|

population. Other |

|

|

|

perceive the |

|

|

possible indicators |

|

|

|

relevance and |

|

|

such as bruises, tattoos, |

|

|

|

utility of sex |

|

|

or brandings were |

|

|

|

trafficking |

|

|

perceived as irrelevant |

|

|

|

indicators. |

|

|

and/or unhelpful in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

identifying ST victims. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cisgender or trans |

|

|

|

|

|

|

males were rarely |

|

|

|

|

|

|

identified as victims. |

|

|

Ramnauth, T., Benitez, M., |

To examine |

Quantitative |

164 registered |

Self-reported |

16.2% of nurses had |

|

Logan, B., Abraham, S. P., & Gillum, D. (2018). Nurses’ awareness regarding human trafficking. International Journal of Studies in Nursing, 3(2), 76. U.S. |

nurses’ awareness of HT. |

|

nurses |

survey |

received training. 11.4% suspected a patient may have been a victim of HT, but only 7.8% reported to the authorities. Reasons for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

this low report rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

include a lack of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

training or guidelines. |

|

Recknor, F. H., Gemeinhardt, G., & Selwyn, B. J. (2018). Health-care provider challenges to the identification of human trafficking in health-care settings: A qualitative study. Journal of Human Trafficking, 4(3), 213-230. US |

To explore healthcare providers’ perspectives on factors inhibiting their ability to identify adult victims of labor and/or sex trafficking. |

Qualitative |

44 participants. 10 (23%) nurses, 9 (20%) social workers, 5 (11%) physicians, 5 (11%) psychiatrists, 4 (9%) medical and 2 (5%) psychiatry residents, 4 (9%) psychologists/psy chotherapists, 2 (5%) healthcareeligibility workers, 1 (2%) unclassified, and 2 (5%) nursing professors. |

Semi-structured interviews. Data collected between June 2015 and February 2016. |

HCPs reported that the number of victims identified was low which could have been related to knowledge gaps. Labor trafficking was rarely addressed. Repeated patient visits led HCPs to dismiss or provide insufficient attention to these individuals. HCPs hesitated to identify patients because of the lack of community resources. They believed there was no help or safe place to refer victims. |

|

Ross, C, Dimitrova, S, Howard, L.M., et al. (2015). Human trafficking and health: A cross-sectional survey of NHS professionals’ contact with victims of human trafficking. BMJ Open; 5:e008682. England |

To estimate the proportion of National Health Service (NHS) professionals who have cared for HT victims and (2) to measure their knowledge and confidence caring for this population. |

Analytical Crosssectional Quantitative |

782 National Health Service healthcare professionals of which 285 were nurses. |

Self-report survey August 2013 to April 2014. 84.4% response rate. |

60.2% of respondents reported low levels of perceived knowledge or preparedness to care for HT victims. 95.3% were unaware of the extent of HT. 7.8% reported having received any training on HT. 76.4% did not realize that notifying authorities could further jeopardize victim safety. 74.6% expressed interest in receiving training. |

|

Ruiz‐Gonzalez, C., Roman, P., Benayas‐Perez, N., Rodriguez‐Arrastia, M., Ropero‐Padilla, C., Ruiz‐ Gonzalez, D., & SanchezLabraca, N. (2022). Midwives' experiences and perceptions in treating victims of sex trafficking: a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(7), 2139-2149. Spain |

To explore the experiences and perceptions of midwives in the treatment of sex trafficking victims. |

Qualitative |

14 midwives |

Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Conducted June 2021. |

Victims are living in situations that impact their mental health and their decision-making capabilities, which in turn influences their ability to seek and accept help. Barriers to seeking help include lack of identifying documents and knowledge of the healthcare system. |

|

Sangha, M. R., & Birkholz, L. (2022). Nurses' ability to identify human trafficking victims. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 39(3), 156-161. U.S. |

To evaluate nurses’ perceptions when identifying HT victims in the acute care setting after a 1hour slide |

Quasi experimental |

72 participants |

Pretest/posttest |

An improvement in RN’s knowledge assessment scores by 19.2% was noted following the education. Nurses also reported an increase in selfefficacy. More than 90% of the nurses incorrectly identified facts regarding |

|

|

presentation |

|

|

|

HT victims. Nurses’ preexisting assumptions may |

|

|

educational intervention. |

|

|

|

be a factor in failing to identify victims. |

|

Wolf, L. A., Perhats, C., & Delao, A. (2022). Educational needs of US emergency nurses related to forensic nursing processes. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 29(1), 12-20. U.S. |

To examine current forensic knowledge and training of emergency nurses and to identify gaps in skills and practice. |

Quantitative |

1,824 Emergency Department Nurses. |

Cross sectional survey. Data collected between October 1 and November 30, 2020. Total response rate 4%. However, 73% of those who opened the email responded. |

64.3% of nurses reported rarely caring for HT victims. 7.4% of nurses reported they felt extremely competent in the care of patients with injuries resulting from HT. 91.2% expressed that most of their colleagues did not have training in forensic nursing. Lack of training resulted in failure to preserve evidence for criminal proceedings. |